With so many wonderful fibers available to handspinners now, a frequent question I get is: what wool or fiber is best for a beginner?

As a new spinner, your first goal is to spin a consistent single; that is, a single with few variations in diameter and the amount of twist throughout its length. To do that, we want to smooth out the flow of fiber through the hands, and minimize starting and stopping.

The fiber we have available to spin has a few characteristics, and each characteristic impacts the ease of spinning.

Fiber preparation: Fiber is most often available as combed top (a fiber mass which has been combed, resulting in aligned fibers of the same length), roving (similar to top, though fibers of different lengths can be included), carded batts, rolags, and punis (carded and rolled masses of fiber), or loose locks.

Spinning is easier when your fibers are not clumped or compacted and can flow evenly through your hands.

Combed top, especially dyed top, becomes compressed in the dyeing and processing. It can help to open the fiber up by pulling on it *slightly*; that is, just enough so that they move, but not so much that you pull tufts out; this can contribute to thick and thin areas in your single.

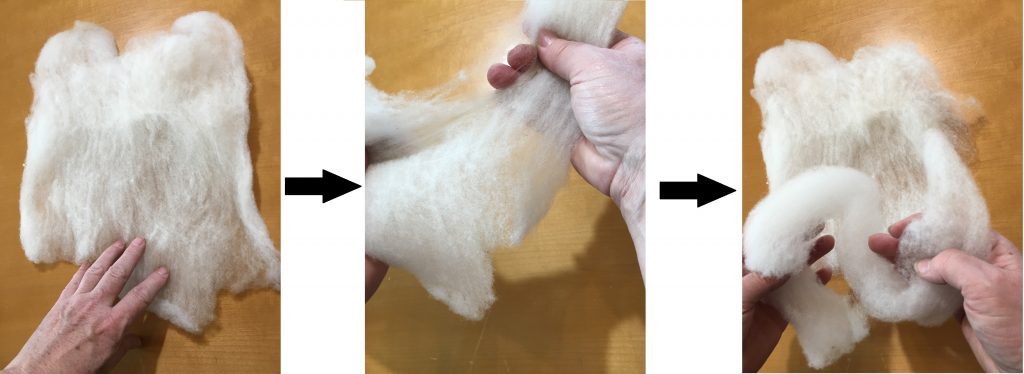

Batts, rolags, and punis can come in amounts that are hard to hold onto, or can get bound up when fiber is pulled from the center. They may be easier to handle if you unroll them and pull off strips. Rolags and punis look like smaller batts. They are sometimes rolled tightly for a purpose, but if the fibers won’t pull easily from the center, you can try unrolling the mass and rerolling it looser.

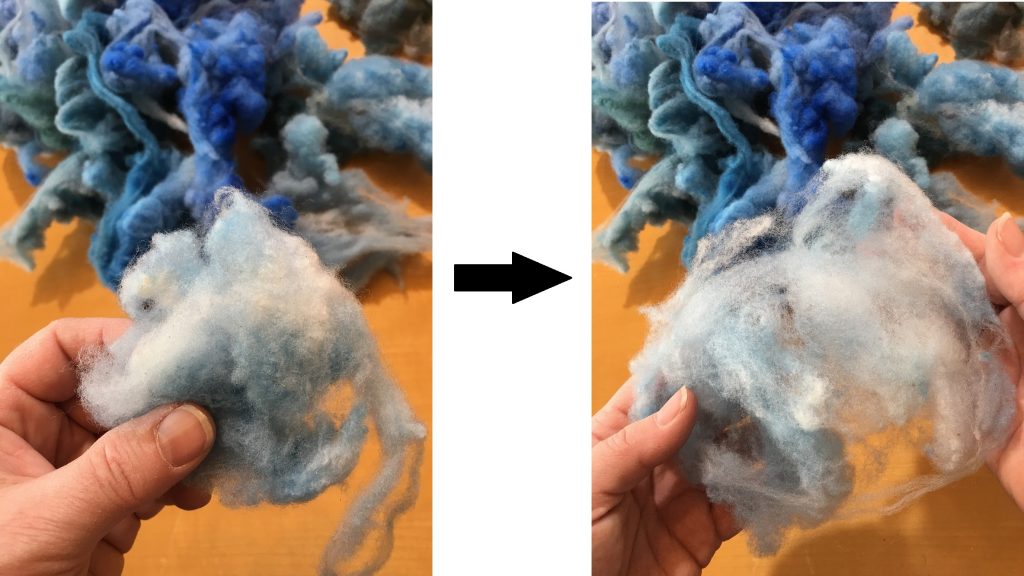

Loose locks are washed and processed so that the locks stay together. To spin a smooth yarn, you can gently pull the locks apart and create a ‘cloud’ of fibers, grabbing small handfuls at a time.

Fiber length (staple length): Fibers can come in lengths anywhere from 1-inch cotton or yak fibers to flax and longwool that reach 12 inches or longer.

Spinning is easier when you work with fiber lengths that are not too short, and not too long.

Very short fibers—under 2”—require twist to enter the mass right away so that they don’t drift apart, and having enough time to draft and treadle on a wheel can be tough for a beginner. On a drop spindle, short fibers are challenging for the same reason; twist needs to enter the mass quickly, before the weight of the spindle pulls them apart. Once you’re comfortable with mid-length fibers, try short fibers, using the fastest whorl you have. For a hand spindle, try these fibers with a supported spindle instead of a drop spindle.

Conversely, very long fibers—5 inches or more—also require some special handling. You have to keep your hands far enough apart (if you’re doing a worsted draft) so that your fiber hand isn’t holding onto the fibers and preventing the fibers from feeding into the twist. However, you still have to control how much fiber goes into the drafting triangle or your entire mass of fiber can end up in there.

You have a few more options with long fibers:

- You can cut them to more manageable lengths

- Once you’re comfortable with midlength fibers, you can learn to spin over the fold.

Fiber texture: As a beginner, you’ll want fibers that pass easily through your fingers, but not so easily that they’re hard to control.

Spinning is easier when you choose fibers of moderate texture: not too slippery, not too fine, not too delicate, not too coarse.

Besides being very long, silk top can be quite slippery. Camelid fibers, such as alpaca, can also be slippery. Very fine and delicate fibers, such as qiviut, yak, or rabbit, while also being short, can mat or felt in your hand, especially if your hands get hot and sweaty, preventing you from drafting it smoothly. Very fine (19 micron or finer) merino wool would also fall in this category. Very coarse fibers may be easily overspun, and you’ll have rope instead of yarn.

Higher micron (21+) merino is widely available as combed top. I wouldn’t recommend it for a very new beginner, because it is still a fine fiber and can mat and stick to itself easily. But, after spinning a pound or so of easier materials, you could try this merino next.

Fiber amount: Too much, and you drop it, or can’t get your fingers around it to manipulate it properly. Not enough, and you’ll be stopping frequently to join a new fiber supply.

Spinning is easier when the amount of fiber in your hand is comfortable to work with.

This is probably the most arbitrary and personalized choice, so this will take some experimentation on your part. The right amount allows you draft properly and easily, allows the fiber to flow through your hands, and is enough so that you don’t have to stop and join a new fiber supply so often that you can’t find your rhythm.

There are a few ways to manage your fiber supply:

–Pull off strips from your batts or top/roving. Pull off strips that are thicker than the single you want to make, and thick enough so that it won’t fall apart in your hands. A strip that is too thin limits your ability to draft properly, too, so experiment with what feels right, and remember that what feels right will change as you practice.

–Hold your fiber supply close to your drafting hand. A distaff is a pole or dowel with a basket or cage at one end. The tool was stuck through the spinner’s belt, and the fiber mass was placed in the basket and fed down to the spinner’s hands. This kept the fiber supply close and oriented so that the fibers could be pulled and drafted easily. You don’t see distaffs in use much today; instead, you can wrap strips of fiber around the wrist of your drafting hand, or keep your fiber in a small bag hanging from your wrist (not too heavy so that you don’t strain your wrist). You could try a hanging basket, too. Whatever you try, the key will be in making sure you don’t have to pull on the fibers too much, and that they don’t fall out of your container.

–Have your fiber prepped and ready to grab. If you’re working with loose locks, have a big pile of them fluffed and separated and ready to go, so you don’t have to stop so much.

So, what does that leave us with? My recommendation is to choose medium to medium-fine wools with staple length of two to four inches, and prepped so that the fibers are loose yet organized. CVM, Columbia, Polwarth, Shetland, and Corriedale wools are great breeds to look for and should not be too expensive or hard to find. If the fiber is in combed top or roving and seems slippery to work with, try carding it into a batt or a rolag, roll it up loosely, and then pull fibers from the center.